Hey there! If you’ve found your way here but are not yet subscribed for the weekly newsletter, you can do that here. You will never miss a recipe or a story, and I’ll be eternally grateful for your support.

Hello The Jewish Table readers!

I’ve got an exciting recipe to share with paid subscribers today for Dried Fruit and Walnut Bread that is just as crusty and chewy and fragrant and packed with deliciousness as you would hope. (And oh my goodness, it is absolute perfection when toasted and spread with a little salted butter.)

But before we get to the recipe, which I developed in honor of the upcoming Jewish holiday, Tu Bishvat, I wanted to share a favorite essay from my personal writing archives.

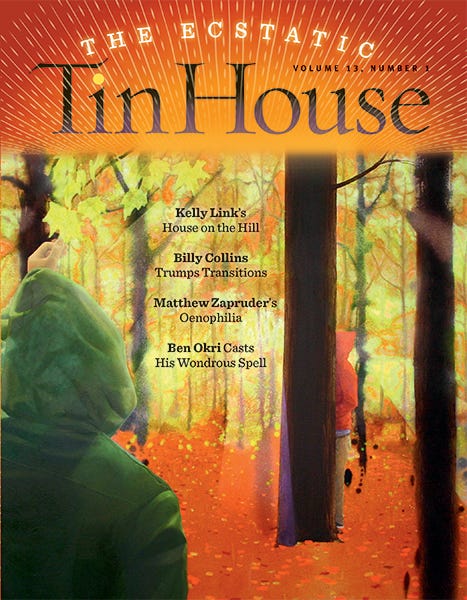

The Four Worlds, was published in 2011 in Tin House—a delightfully eclectic, but also grounded, literary magazine that ran for 20 years. (Tin House remains an independent book publisher, but the magazine’s last issue was released in 2019.)

As a relatively new writer, I remember the *absolute thrill* of having my work published in Tin House—a magazine that had also published literary greats like Billy Collins, Yehuda Amichai, Miranda July, Alice Munro, and for heaven’s sake, Pablo Neruda. It was one of those validating moments along a writer’s journey where you briefly feel like, “Gosh, maybe I am doing the right thing with my life after all?” Don’t get me wrong, I think they paid me about 30 cents a word for my efforts—but still.

The essay recounts a Tu Bishvat seder I attended in a crowded Brooklyn apartment in my very early 20s. Think: vegan snacks! Ceramic mugs filled with wine! Flowing hippie skirts! Dark curly hair under crocheted kippot! Lots of soulful communal singing! A not-insignificant amount of body odor! And a very uncomfortable baby Leah who ever so desperately wanted to fit in.

It also does a really great job (if I do say so) explaining just what the heck Tu Bishvat is, and how it evolved from its roots as a tax holiday in ancient Israel, to the spiritual darling of the Jewish mystics, to today’s Jewish equivalent of Arbor Day. If you just want the recipe, feel free to scroll right past the essay. Otherwise, here’s a glimpse into one of my favorite early pieces.

The Four Worlds

By: Leah Koenig

Originally published in Tin House, Vol 13 No 1 (Fall, 2011)

One night in the depths of a snowy New York winter, I found myself squeezed into a friend’s steamy Brooklyn living room with about forty people. The space was draped with colorful tapestries and adorned with candles and pillows to cushion the bottoms of those of us not settled onto one of the rumpled couches. The scent of sweat and tea tree oil hung in the air, and the drone of overlapping conversations filled the room.

We were there to celebrate Tu Bishvat – a minor Jewish holiday colloquially known as the “New Year of the Trees.” Growing up as a religiously clued-out Jew in suburban Chicago, Tu Bishvat had never blipped my radar. Now I was surrounded by a group of fellow twenty-somethings who had purposefully set aside a Tuesday night to celebrate a Jewish tree holiday.

This should have made me happy. I had graduated from college just seven months earlier, tucking my freshly minted environmental studies degree into my backpack and, like so many wide-eyed graduates, pointing my compass towards New York City. During college, I had reconnected with Judaism after taking a world-rocking class called Judaism and Ecology. Up until then, religion had always felt extraneous, something to dread or ditch. Now, I buried myself in books with titles like Torah of the Earth and The Splendor of Creation: A Biblical Ecology, and marveled how an ancient religion – one that had once guided nomadic shepherds and land-tending farmers, my ancestors – could feel so relevant and alive. New York, with its public transit system, urban gardens and vibrant Jewish community, seemed like the ideal setting to live out my newly awakened religious consciousness. And this Tu Bishvat gathering, I hoped, represented an initiation into my next phase of adulthood, and acceptance into a new community of friends.

Shortly after arriving, however, I began to feel uneasy. Scanning the room, I saw women with long tunics flowing over linen skirts, and men with dark scruffy curls peeking out from under knit caps. Someone was thumping on a hand drum, a few massage circles had started up, and an air of spacey satisfaction permeated the room. Feeling erroneously dressed in jeans and a sweater, and edged out of the earnest conversations around me, I started to doubt whether I was actually surrounded by kindred spirits. I checked my watch. We had been sitting there for nearly an hour, with no indication that the evening’s main event, a Tu Bishvat seder, was about to start. Was I the only person thinking it was getting late for a work night?

Tu Bishvat (literally the 15th day of the Hebrew month of Shvat) was not always the Jewish calendar’s totem eco-holiday. It started rather mundanely as a tax day – the ancient Israelite’s equivalent of April 15th. The holiday marked the moment in late winter when the sap in fruit trees was said to rise again after the dormant, rainy winter. Any fruit produced before Tu Bishvat legally belonged to the previous fiscal year, and anything that sprouted after it to the New Year.

There may be some poetry in the notion of a New Year for the trees, but not mysticism. That came generations later in sixteenth-century Tzfat (Safed), which at the time was a flowering center of Jewish mystical thought. With its focus on learning and law following, mainstream Judaism can sometimes feel void of passion. The Jewish mystics, on the other hand, hurled themselves towards joy. They sought out the pure white spaces in between the lines of text – the ecstatic union of religion and spirit. The tree is a powerful and primary image in Kabbalah, and Tzfat’s mystics – who believed that glimpses of God are reflected in the natural world – recognized an untapped spiritual and metaphorical potential in a tree-centered holiday. Over time, they developed an elaborate four-part seder, loosely modeled after the Passover seder, that tapped into the day’s inherent themes of rebirth and regeneration.

In college, I had read with enthusiasm about the four parts (or “worlds,” as the mystics called them) of the seder, and how each one represented an ascending state of being. Assiyah, the first and lowest world, was the realm of human action. One step up was yetzirah, the world of emotion, followed by briyah, the world of thought and analysis. The final world, atzilut, represented the realm of Godly perfection and spirit – the realm towards which the mystics zealously reached. Each symbolic world had a glass of wine associated with it (an all white cup in the first world that gradually progressed to all red by world four), and a category of fruits and nuts that acted as the seder’s ritual centerpieces.

In the first world, the mystics dined on fruits with inedible peels and squishy middles – things like oranges and walnuts that symbolized an earthly realm where people require hard outer coverings to protect their vulnerable insides. World two brought plums, dates and olives – fruits with fleshy outsides and hard pits to mark a shift into a world of increasing inner emotional strength. Next came entirely soft and edible fruits – things like figs and grapes to symbolize a world where all defenses can finally relax. World four had no corresponding fruit. The realm of the Divine, the mystics thought, simply transcended anything so physical.

As the wine at their seder flowed, the incense burned and their singing intensified, the mystics blessed and ate these fruits. In doing so, they propelled themselves increasingly higher through the worlds and closer to Divine unity. The beginning of the seder, which was first written down in 18th century Venice in a document called Peri Etz Hadar (fruit of the lovely tree) began:

May it be your will O Lord our God and the God of our Ancestors, that through the sacred power of eating fruit, which we are now eating and blessing, while reflecting on the secret of their supernal roots upon which they depend, that shefa (favor, blessing, bounty) be bestowed upon them…

The mystics believed that humans have the power to shape the universe through their actions – and their Tu Bishvat seder was nothing short of gastro-magic.

Tree exultation, esoteric ritual, and vegan-friendly snacks – these are the things that get Jewish environmentalists excited. Four hundred years after the Peri Etz Hadar was written, and worlds away in Brooklyn, my new acquaintances were raring to dive into our own seder. In front of us a long, low table groaned under the weight of wine bottles and ceramic mugs. Immense fruit platters glistened with orange and grapefruit moons, bowls of jewel-like raspberries, pistachios and macadamia nuts, slick black olives, figs and dates like congealed honey and fresh persimmons, sliced and dripping. A separate table nearby held garlicky homemade hummus, plates of cheese, and loaves of seed-encrusted challah – food to fuel our bodies as the seder fueled our souls.

I had never seen such an elaborate feast, or a spread where nearly every food came so lushly wrapped in metaphorical significance. Normally at events, I rely on the food table to distract me from moments of social discomfort. But here, the treasures before us were off-limits until the seder reached the corresponding world. Meanwhile, I was left alone with my fidgety hands and the growing feeling that I did not quite belong.

Eventually Noam – a bearded Vancouver transplant who was a central figure in Brooklyn’s eco-Jew scene (and whose apartment we were sitting in) – stood up and hushed the conversation by launching into a niggun, a soulful wordless melody. The room swelled with song as everyone, clearly familiar with the tune, joined in. I listened, struggling to catch on.

The seder, Noam announced, would be led by all of us together in a collaborative journey. Unlike virtually every other Jewish holiday, he said, Tu Bishvat had no prescribed rules, which meant the evening was ours to shape. The crowd murmured its approval, while I suddenly felt like I had sucked in the contents of a balloon. Collaborative journeys sounded dangerously unstructured. As a chronic overachiever with the nagging fear that I was never as capable as I had tricked people into thinking I was, I found improvisation unsettling. Terrifying, really. In dance class as a kid, I loved learning new routines from the teacher, but dreaded the moment at the end of class when everyone stood in a circle and took turns dancing alone in the middle. There was too much risk involved – too many opportunities for failure.

Before I could plot my escape however, the first glasses of wine were poured (all white to symbolize the depths of lifeless winter where the seder begins). We blessed the wine – Blessed are You, the Lord our God, King of the Universe, Creator of the fruit of the vine – toasted l’chaim and drank. The seder creaked slowly to life, beginning its meandering pathway through the four worlds. Along the way, people shared passages from the Torah and Talmud, a smattering of ecological thoughts, and blessings for the group. One woman, a spiky-haired puppeteer, used a large turtle puppet to tell a story about the Jewish calendar’s connection to the cycles of the moon. Next, a man read a quote by the rabbi and civil rights activist, Abraham Joshua Heschel: “The root of religion is the question what to do with the feeling for the mystery of living, what to do with awe, wonder and amazement.” “Psssshhhhh…” answered the crowd, exhaling in audible delight. “That’s holy brother,” said the guy sitting next to me, while I squelched the urge to roll my eyes.

In world two, a woman with purple plastic-frame glasses and her shoulders swathed in a colorful scarf coaxed everyone to standing and guided the entire mass of us into the yoga tree pose. “As you breathe in, imagine you are a tree waking up from winter,” she said. “Feel your feet rooted firmly in the ground, and the sap spreading life into your thirsty limbs.” Another collective sigh reverberated through the room, now full of energized, life-filled trees. I wondered if perhaps my own sap had run out, or gotten clogged at my feet. It wasn’t the message that was the problem – I had drunk plenty of eco-Jewish Kool-Aid. Still, something felt decidedly wrong. I felt so self-indulgent standing in a sweat-soaked Brooklyn living room, eyes closed, pretending to be a tree. It was so decadent, so cloistered from reality. On the other hand, I could not deny that I was jealous. I craved the dreamy effortlessness I saw in the Jewish hippies around me. I envied their willingness to, like the mystics once did, flop like rapturous fish in the cool waters of spiritual bliss, while I sat on shore crafting excuses to stay dry.

The night ambled forward into world three, and there was more singing – a mixture of Joni Mitchell, Pete Seeger, and the energetic tunes of the 20th century neo-Hasidic rabbi, Shlomo Carlebach. There was more drinking too. I could feel my edges slowly softening and my cheeks blushing as the red wine – representing fire and life – mingled with, and then slowly took over the white wine in my mug. And at the end of each world, there was fruit. Before eating, Cody, a crinkly-eyed earth mother, would lead the group in a meditation on the sensual, sacred act about to take place. Each bite, she said, had the double purpose of delighting our taste buds and also bringing our consciousness ever closer to each other and the Universe.

Throughout the evening I ate obediently, consuming a salad’s bar worth of fruit and hoping for a lightening bold of connection. Now, I held a raspberry in my mouth, feeling its gentle push back against my tongue. How perfectly and unapologetically red it is, I thought, biting in. How utterly content to be itself.

World four came rolling in well after midnight. The table in front of us was now covered with peels and pits and splashes of wine. Someone shut off the lights as Noah lit a candle, which he held above his head. In world four we would eat no fruit, he reminded us. There was just the candle, the light of God’s presence, and the Divine glow emanating from within each of us. The singing had stopped and all forty of us sat in silence. In the darkness, for the first time that evening, I felt fully at ease – my belly distended with fruit and my whirring mind hushed with wine. A crisp breeze came rustling through an open window, sending a spray of goose bumps down my arms and I breathed in deeply. Tomorrow morning I would be back to work – probably with a hangover. It was unlikely I would ever invest in a collection of linen skirts, or be fully embraced by the community around me. But tonight in my new Brooklyn home, if only for a moment, I was open to accept the sap.

Dried Fruit and Walnut Bread

This is some seriously delicious bread. Baked in a Dutch oven, it has a hearty, crunchy crust and a wonderfully chewy crumb. It comes perfumed with cinnamon and loaded with walnuts and dried fruits like raisins, dried cherries, figs, apricots, and dried apples— baker’s choice on which fruits at what ratios.

The TL:DR from the essay above is that a Tu Bishvat seder features different categories of tree fruits that connect symbolically to the Jewish mystics’ understanding of an earthly-spiritual continuum. This bread won’t automatically turn you into a mystic, but it is definitely packed full of goodies grown on trees.

Whether you are hosting a Tu Bishvat seder of your own, want to celebrate the Jewish tree holiday with something tasty, or are simply craving a week of really great breakfasts, this loaf has you covered. Slather toasted slices with butter and honey, peanut butter, or whatever you’d like—now that’s some divine stuff, right there.

The loaf’s texture is best when made with bread flour, but you can substitute all-purpose flour in a pinch.

Next week’s newsletter—with a recipe for chicken pot pie bourekas (with a gluten free option!)—will go out to all subscribers. But this week’s recipe is for paid subscribers only. Update to a paid subscription here or below.

Makes 1 loaf

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Jewish Table to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.