Tea from a Coffee Pot

What kitchen object feels most like home to you?

Hello The Jewish Table Readers,

One of my on-going goals is to read more books (at home, on the subway, in waiting rooms etc.), with the hope that I will stare less at my phone. It is a constant battle—screen-induced dopamine is wickedly powerful stuff. But I recently finished a book that managed to wrench my attention away from the screen for many delicious minutes at a stretch.

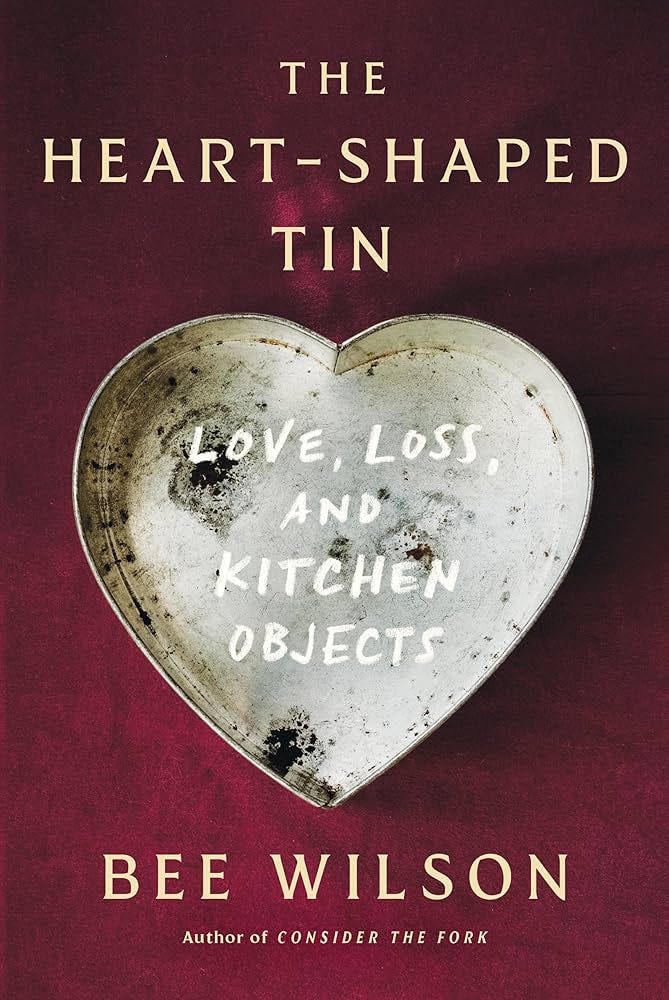

The book is The Heart-Shaped Tin: Love, Loss, and Kitchen Objects by Bee Wilson. (She also has a newsletter on Substack called Until Golden.) Wilson and I share an incredible publisher (W.W. Norton) and an equally incredible editor (Melanie Tortoroli), and I was fortunate enough to snag a copy of The Heart-Shaped Tin recently while visiting Norton’s office in Manhattan. (Wilson lives in the U.K. but was in New York for press events and happened to be signing copies of her book at the office the day I stopped by.)

I tucked the book away in my bag, and forgot about it for a couple of weeks. But eventually, the metal tin on the cover, with its darkened patches of oxidation and years of love and use beckoned me in. After reading Wilson’s first paragraph, I was a goner:

“I have long felt that kitchen objects can have a life of their own. Even so, I found this eerie. One August day in 2020, I was going to fetch clothes out of the washing machine when suddenly a cake tin fell at my feet with a loud clang. It wasn’t just any cake tin. It was the heart-shaped tin I had used to bake my own wedding cake. I wouldn’t have thought much of it except that it was only two months since my husband had left me, out of the blue.”

With intrigue and emotional weight like that, how could I not keep reading? The Heart-Shaped Tin stitches together a collection of essays that explore the significance and energy a kitchen object can hold and, at times, radiate into our lives.

Wilson writes about a silver-plated toast rack—a defining feature of her mother’s daily breakfast routine, which became a symbol of loss as her memory was stolen by dementia. She writes about a vegetable corer that a Syrian chef left behind, along with pieces of his heart, when he moved to London; a metal spoon forged as an act of resistance by a Polish-Jewish tailor in a Nazi prison camp; a broken cup mended by the Japanese art of kintsugi (“mending smashed crockery with seams of precious metals”); a flimsy-looking aluminum pot that a friend transforms, with the alchemy of love and intuition, into the ideal rice cooker; a pale blue Wedgwood teapot purchased on eBay that, coincidentally, Wilson’s own grandfather helped design.

“We only get one life and it is often cruelly short,” Wilson writes. “But the magic of things is that they can live more than once, passing faithfully through many pairs of hands, gaining different meanings each time. Our most significant kitchen objects can keep us connected with the dead and the absent, so no wonder we sometimes act as if they were charmed.”

—

I have never been much of an acquirer of things. I love looking at and being near beautiful things, of course. A mason jar filled with tulips, say, or a fat cluster of translucent purple grapes in a ceramic bowl on the counter. But I don’t like having a lot of “stuff.” I will always prefer experiential gifts—shared time doing something fun with people I love—over any physical item. And if our home was, God-forbid, on fire, there are only a handful of precious objects I would instinctually grab. (Assuming all family members were already safe and accounted for.)

I would scoop up the photo books I’ve made for my children every year for their birthdays, chronicling their year of growth and the people who love them. And I would leap over a burning chair to take the wooden gefilte fish bowl and chopper my great grandparents brought with them to America from Eastern Europe long ago. And which my family growing up, and my family today, used/uses as a candy bowl. (I’d leave the candy behind.)

But as much as I love and rely on it, I would not grab my French press coffee pot. Yoshie and I use our stainless steel Mueller French press every single day. It floats from countertop to table and back on weekend mornings. And our kids know that the day hasn’t really started until the gooseneck water kettle is flipped on, yesterday’s coffee grounds have been thoroughly scraped out and washed away, and today’s coffee grounds are steeping.

More recently, I have started brewing an afternoon pot of black tea in our French press, enjoying the day-brightening ritual of plunging loose tea leaves through hot water, and stirring my cup with a generous dollop sour cherry jam, just like my Jewish ancestors did. It is a change in routine for our beloved French press, but she has taken to the evolution with (ever so slightly coffee-scented) grace.

And still, I would not rescue the French press from a burning building. Because, as with so many modern items, this coffee maker is eminently replaceable. My great grandparents’ bowl is fashioned from a solid piece of wood from a tree felled more than a hundred years ago somewhere in the Pale of Settlement. There is no company name etched or scrolled across the bottom—just sturdy, anonymous craftsmanship built to last through generations. My French press, meanwhile, was built to be replaced often and as needed, with the flick of the fingertips online.

I wonder, reading Wilson’s book, what my generation will have to pass down to our children. What will they remember us by? What will they take comfort in once we are gone if most everything today is built to be disposable and replaceable? Will they really want our chipped Ikea plates? It is a line of questioning that makes me a bit sad.

But ultimately, it is not up to me—or any of us—to decide which objects the next generation will cling to as relevant or special. Maybe for my children, like for me, it will be the family gefilte fish/candy bowl. Perhaps it will be the French press even if, by the time they inherit it, the plunger filters have been replaced multiple times. Maybe it will be something that I haven’t even clocked as particularly significant, but that they will attach meaning to. Whatever items they gravitate towards, I hope they will feel my love billowing outward, warm and comforting like steam from a coffee pot.

Please share in the comments: What kitchen object feels the most like home to you? How did it come into your life? Who/what does it remind you of? How do you use it?

Black Tea with Sour Cherry Jam

Level up your tea time by serving this sour cherry jam-swirled black tea with Cinnamon-Almond Rugelach, Chocolate-Cherry Mandelbrot, or Plum Cake Muffins.

Serves 1 or 2