Discover more from The Jewish Table

This week’s newsletter and recipe are just for paid subscribers of The Jewish Table. But you’re in luck because through Sept 6th, new paid subscriptions are 20% off! Get in on the cooking fun, plus access the full recipe archive, by upgrading to a paid subscription. Thank you! xo

I was a vegetarian for 10 years (vegan for two) from the late 1990s through the mid 2000s. I learned a lot during those years, including that dairy-free ice cream was pretty terrible (there are significantly better options now!) and how to make a tofu stir fry that doesn’t suck (higher heat, larger surface area, pan fry or roast the tofu separately from the veggies.)

But the main lesson I took away from that time period was that lots of folks found the idea of a Jewish vegetarian absolutely bonkers. No brisket? No chicken soup? No sweet and sour meatballs? Won’t you starve? How can you even celebrate a Jewish holiday without meat? You won’t even try a bite?

For 10 years, every Jewish holiday meal I attended came with a side order of incredulity. I basically lived inside the infamous “I’ll make lamb!” scene from My Big Fat Greek Wedding.

Things have fortunately changed over the last decade and a half since—and not just because I started adding meat back into my own diet. More folks seem tuned into the fact that Jewish vegetarianism actually has longstanding precedent. (For more on the history of Jewish vegetarians in Europe and America, including Isaac Bashevis Singer’s justification for going meat free in his 50s, check out my article below the recipe.)

More importantly, there seems to be much less collective tsuris these days from Jewish home cooks about their vegetarian relatives and friends. Do I still get the occasional, “What the heck am I supposed to make for my vegan daughter on Passover?” question at cooking demo events? Sure. But for the most part we have moved beyond our surprise that Jewish vegetarians exist (according to the Pew Research Center, about 3% of American Jews today identify as vegan/vegetarian), and moved towards finding ways to welcome our meat free fam to the table.

At least some of this progress has to do with better culinary guidance. From Gil Marks’ trailblazing, 2004 Olive Trees and Honey, to Paola Gavin’s Hazana: Jewish Vegetarian Cooking from 2019, and Micah Siva’s Nosh published earlier this year, joyful, delicious, plant-based Jewish recipes abound.

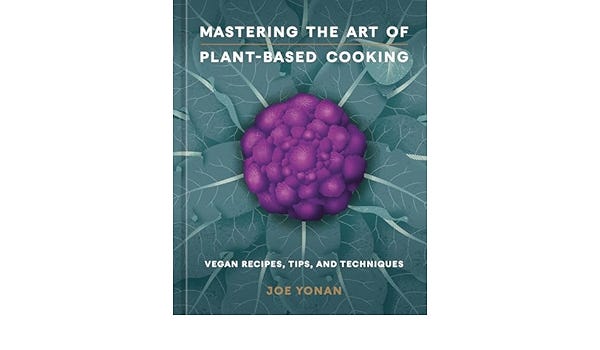

Beyond the Jewish publishing world, the number of vegetarian, vegan, and vegetable-forward cookbooks has absolutely exploded in recent years. One of my new favorites is called Mastering The Art of Plant-Based Cooking, published this week by Joe Yonan. Yonan is the food editor at The Washington Post, and also a long time proponent of meat-free cooking. And while his new book isn’t Jewishly focused, it is filled with globally-inspired recipes (Skillet Spanakopita, Whole Roasted Cabbage with Potatoes and White Beans, Lasagna with Cauliflower Cashew Béchamel) that would be right at home on your holiday table.

What I love most about Yonan’s book is his insistence that plant-based cooking should not be defined by what’s “missing” (namely: meat, dairy, and eggs). Instead of comparing every vegan dish to some meat-centric status quo, Yonan suggests switching our mindset towards the abundance of ingredients and culinary creativity available to the plant-based cook. “Plant foods deserve accolades because of their own outstanding qualities,” he writes in his introduction. “Love them for what they are, not for what they’re not.”

I also appreciate how the book guides home cooks towards a more improvisational, free-wheeling (with structure) approach to cooking. For beginners who prefer step-by-step instruction, there are plenty of “do this, then do that” recipes—like for Lentil-Chickpea Meatballs in Tomato Sauce and Jeweled Cauliflower Rice. But for home cooks with a little kitchen experience under their belts and a desire to trust their instincts more, the book also includes many recipes that let you choose your own adventure.

Take the Nearly-Any-Vegetable Coconut Soup. Instead of specifying what type of onion to use, the recipe calls for “8 to 12 ounces of alliums” (your choice of scallions, leeks, or onions). And instead of prescribing a certain amount of fresh herbs, cooks can add “up to 1 tablespoon chopped woody herbs (thyme, rosemary, sage).” The 13.5 ounce can of coconut milk is required, but the vegetables you pair with it—anything from spinach to kabocha squash, to mushrooms—is up to you.

In other words, the recipe doesn’t simply teach you how to make a particular soup. It imparts the framework (and confidence) you need to create a satisfying soup with whatever you happen to have on hand. This type of freedom might feel overwhelming at first. And in the hands of a true beginner, it could lead to some funky, oddly spiced concoctions. But every path to mastery includes a few bumps along the way, right?

Yonan also throws frazzled cooks a life raft by offering three possible riffs on the Nearly Any Vegetable Coconut Soup—a carrot-coriander version, a lemony spinach version, and a zucchini thyme version. I chose the zucchini version, adding a few flourishes (fresh basil and handful of chopped tomatoes) based on farmer’s market veggies I had purchased over the weekend.

I’ve shared my take on the recipe below, but I encourage you to check out Yonan’s book for a delicious deep dive into plant-based cooking. Whether you are vegetarian/vegan yourself, cook for a meat-free loved one, or just want to serve Caramelized Onion Dip (made from cashews, not dairy!) with challah at your next meat-based Shabbat dinner, it absolutely deserves a place on your cookbook shelf.

Zucchini Coconut Soup

Recipe adapted from Mastering The Art of Plant-Based Cooking, by Joe Yonan (Penguin Random House, 2024)

Serves 4 to 6

3 tablespoons extra-virgin olive oil

1 medium yellow onion, chopped

4 garlic cloves, chopped

1-inch piece fresh ginger, peeled and sliced

Kosher salt and freshly ground black pepper

1 tablespoon chopped fresh thyme

1/4 to 1/2 teaspoon red pepper flakes

1 1/2 pounds (675 g) zucchini, unpeeled and chopped

1/2 pound (225 g) ripe tomatoes, chopped

One 13.5-ounce (400 ml) can full-fat coconut milk

1/4 cup (10 g) fresh basil leaves

1/2 teaspoon grated lemon zest

1 tablespoon fresh lemon juice

In a large soup pot, heat the oil over medium heat until it shimmers. Add the onion, garlic, and ginger. Season lightly with salt and cook, stirring occasionally, until softened and lightly browned, 6 to 8 minutes.

Add the thyme, red pepper flakes, zucchini and tomatoes and stir until the vegetables are coated with the spices and fragrant, about 1 minute. Add 2 tablespoons of water, cover the pot, reduce the heat to medium-low and cook, stirring once or twice, until the vegetables are tender, 5 to 10 minutes.

Add the coconut milk. Fill the can with water and add it to the pot. Increase the heat to bring to a simmer, then reduce it to maintain a gentle simmer and cook until the soup is hot and the flavors have melded, 5 to 10 minutes. Remove from the heat and stir in the basil, lemon zest, lemon juice, 1 teaspoon salt, and a generous amount of black pepper.

Working in batches as necessary, transfer the soup to a blender, being careful not to fill it more than halfway, and blend until smooth. (You can also use an immersion blender to puree the soup directly in the pot, though it might not get quite as smooth.) Add more water, as needed, until you reach your desired consistency. Taste and add more salt or pepper, if needed. Serve hot.

Article Flashback / Bonus Reading

Vilna’s Moosewood Cookbook

By: Leah Koenig

Forward, October 5, 2011

When most people think about the early high priestesses of vegetarian cooking, chefs and cookbook authors like Mollie Katzen, Deborah Madison and Madhur Jaffrey come to mind. Now, the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research in New York City is adding another name to the list: Fania Lewando. Next spring, YIVO will publish an English translation of Lewando’s Yiddish-language “Vegetarish-Dietisher Kokhbukh,” the “Vegetarian Dietetic Cookbook.”

Originally published in Vilna in 1938, Lewando’s work is arguably the most ambitious, comprehensive Jewish vegetarian cookbook in existence. It contains 400 meat-free recipes, including Ashkenazi dishes like kugel and blintzes, and vegetarian adaptations of traditional meat dishes, like cholent and schnitzel. Lewando, who owned a well-respected vegetarian restaurant in Vilna frequented by distinguished locals from artist Marc Chagall to poet Itzik Manger, was also an imaginative and prolific recipe developer. Her cookbook also includes “exquisite, original dishes like pan-fried dumplings filled with sautéed mushrooms, vegetable-stuffed tomatoes, and rice with strawberries, which came directly out of her brilliant mind,” said Eve Jochnowitz, a Jewish culinary historian and the book’s translator.

Yet Lewando’s vegetarian lifestyle was hardly commonplace in the early 20th century. Then, as now, traditional Ashkenazi Jewish cooking favored meat — even cheap cuts simmered until tender — over anything green. As American cookbook author Jennie Grossinger commented later in “The Art of Jewish Cooking” in 1958, “Vegetables are comparatively unimportant in Jewish homes.” Lewando was certainly a crusader for fresh produce — but she was not alone. In the decades before World War II, America and, to a lesser extent, Eastern Europe flourished with small but robust pockets of Jewish vegetarian thought.

According to “Vegetarianism and the Jewish Tradition” by Louis Berman, the first modern Jewish writing on a meat-free lifestyle, “The Theory of Vegetarianism” by I.B. Levinsohn, appeared in 1884 in St. Petersburg, Russia. Vegetarian pamphlets, one rather pompously titled “The Torah of Vegetarianism,” and two short-lived Yiddish vegetarian journals were published in the United States around the turn of the century. Lewando’s cookbook, which stands out for its elegance and expansiveness, was predated by several shorter works by others like, the “Vegetarish Kokh Bukh: Ratsionele Nerung,” (“Vegetarian Cookbook: Rational Nutrition”), featuring an early recipe for veggie burgers bound with matzo meal and pine nuts.

In New York City, in the 1930s vegetarians — Jewish and otherwise — could dine at Schildkraut’s, a kosher-style restaurant chain (and later vacation resorts) run by vegetarian proprietress Sadie Schildkraut. In a 2007 article in the Forward, Jenna Weissman Joselit writes that Schildkraut’s “advertisements appeared frequently in the Yiddish- and English-language Jewish press extolling the virtues of Nutolin, Nutose and Protose….” — vegetable meats akin to those made today by Tofurky or MorningStar Farms.

Lewando and her contemporaries would be considered ovo-lacto vegetarians today, meaning they ate dairy and eggs, but no meat or fish. The justifications then for avoiding meat, like those today, were varied and complex. In America, they were likely influenced by the writings of 19th- and early 20th-century health and temperance activists like Sylvester Graham and John Harvey Kellogg, who believed that meat consumption led to physical ailments from indigestion to over-stimulation of the body. As historian Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett wrote in an encyclopedia entry on cookbooks for “The YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe,” a 1907 pamphlet by N. J. Kvitner “stressed the health benefits of a vegetarian diet, including its value in preventing children from maturing sexually too early.” Lewando paired her recipes with essays about vitamins and hygiene (information that would, no doubt, be regarded with skepticism by today’s nutritionists), and an introduction that proclaimed fruits and vegetables healthier than meat.

Many other vegetarian enthusiasts were opposed to animal cruelty. Isaac Bashevis Singer, who famously turned vegetarian in his mid-50s, once said, “I did not become a vegetarian for my health, I did it for the health of the chickens.” And, in Yiddish, ”The Vegetarian Hymn” (Yes, there was one!) read: “Blessed be he who has the courage not to eat meat, not to spill blood! Blessed be he whose humane heart protects every creature from pain and suffering.” Additionally, many of these vegetarian Jews — a largely secular, politically oriented bunch — likely saw vegetarianism as a moral stand-in for the laws of kashrut that they had shed. “Although they no longer kept kosher, there was still a need for boundary and structure,” Jochnowitz, the translator, said. “Vegetarianism offered a combination of ethics and daily practice that filled that need.”

These early restaurants and cookbooks may not have made much of a dent in the Jewish community’s overall meat consumption, but the stirrings of a movement were evident. Today, 73 years after Lewando’s cookbook was first published, vegetarianism has joined mainstream society — making now the perfect time to translate the book (of which only a handful of original copies remain) and introduce it to a new generation. Jochnowitz, who has been a vegetarian for 30 years and is founder of the bilingual Yiddish food and recipe blog In Mol Araan, seems tailor-made for the task. “The minute I first saw Lewando’s book [in 1994], I knew I had to do something with it,” she said. “I immediately connected with her combination of tradition and innovation.”

The revitalized book, which will be published on Mother’s Day in 2012, will maintain Lewando’s confident, gourmet cooking style and the book’s gorgeous color illustrations of seed packets and vegetables, including beets, red cabbage, squash, onions, parsley, cauliflower and green peas. Jochnowitz does, however, plan to convert the recipes from their original metric measurements to imperial and adapt them for the modern kitchen and the contemporary palate. “She tended to cook vegetables a little longer than we would today,” Jochnowitz said. Even so, Lewando’s sophistication and flavor-focused approach to vegetarian cooking were at once timeless and ahead of their time.

Subscribe to The Jewish Table

recipes + stories from the world of jewish food, by leah koenig

Thank you for this education in vegetarian Jewish cooking! We keep a traditional kosher home, but our daughter has been a vegetarian from infancy on. With her it's not an ersatz religion; she simply never liked the taste of meat or fish. Thus I've become quite adept at always serving a substantive side dish with the main course, so she also has something satisfying to eat. She does report encountering the same "What do you eat?" attitude in other Jewish homes. Meanwhile, we've got a vegan daughter-in-law, which has added another complexity to our holiday meals, so I will definitely try your soup here!