Hello! Have you ever tried to make a recipe your grandmother (or other cherished elder) wrote down for you, and it turned out all wrong? If so, you are definitely not alone. In this week’s newsletter, I explore the puzzlingly universal phenomenon of our beloved bubbes lying to us (maybe?) about their recipes.

But first, let’s take a quick look at The Jewish Table over the last month. To those of you who aren’t subscribed to the weekly newsletter yet, here’s what ya missed:

A Miso Mushroom Sipping Broth recipe that was the perfect thing to break the Yom Kippur fast with, and delicious anytime.

An essay about my Relationship to Yom Kippur Fasting, plus the Hungarian Jam Kugel recipe from The Jewish Cookbook.

A dispatch from Sukkot in Rome, where I freaked out at my good fortune to spend the week researching my forthcoming Roman Jewish cookbook. Plus a cozy recipe for Silky Roasted Squash Puree.

A decadent Onion-Sour Cream Tart (Zwiebelkuchen), and a shiny new newsletter column: Adventures in Cooking My Cookbook Collection! First up: The Molly Goldberg Cookbook from 1955.

Never miss a recipe or story! Subscribe to The Jewish Table’s weekly newsletter.

Okay, back to those lying grandmas. My mom’s cousin Ellen, I’m told, was an exceptional home cook - the kind of cook whose dishes were the hit of dinner parties and who always got asked for her recipes. The problem was, I’m also told, she guarded those recipes like a prize. And when she did share, everyone suspected that she left out a key ingredient or two, hampering the efforts of anyone who tried to make them.

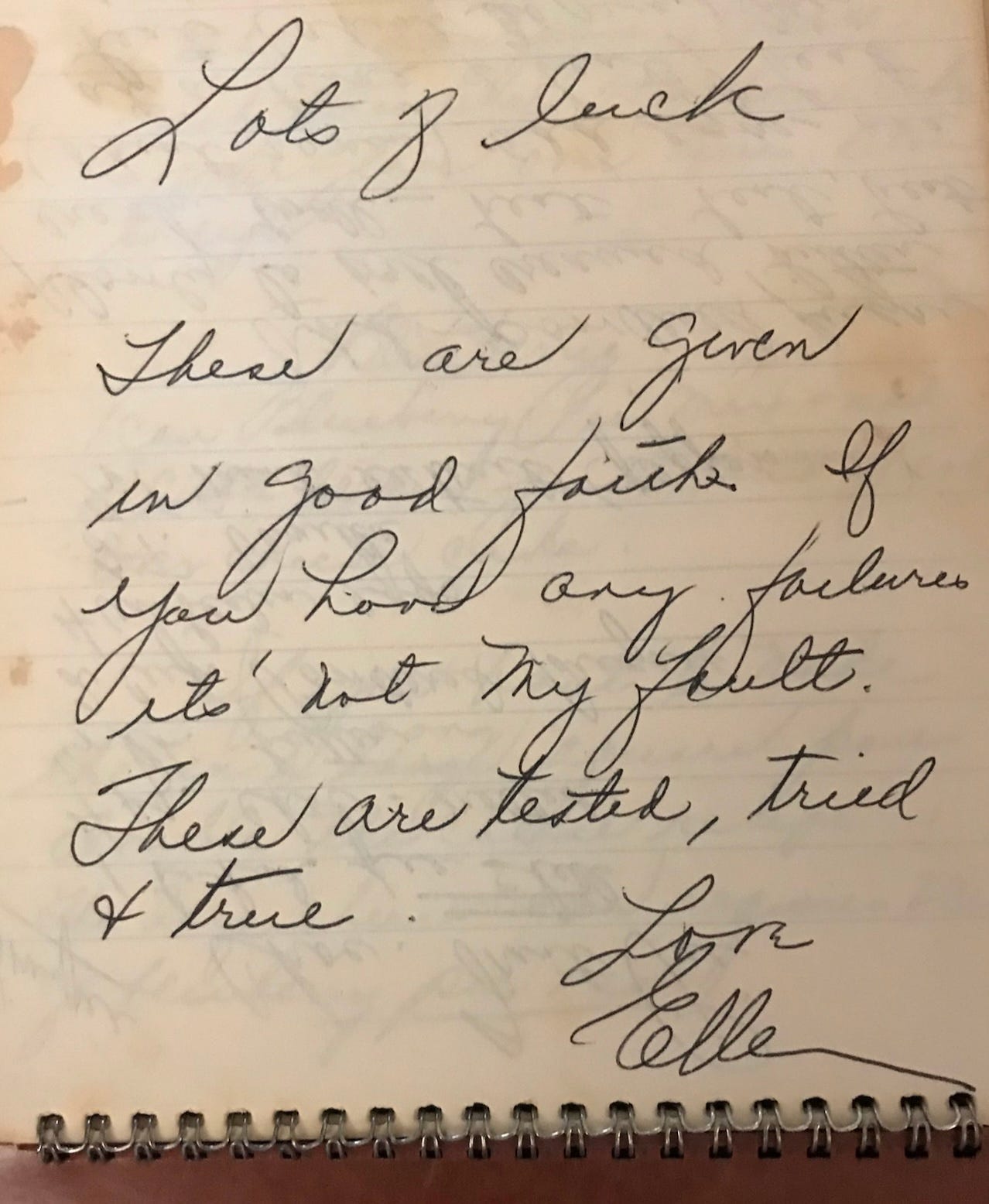

On my mother's cookbook shelf, there's a hand-written, spiral bound recipe collection from that same cousin. After years of nudging by various family members, she was finally convinced to write down her greatest hits - for real this time. In the back of the book, in lovely script, she wrote:

Lots of Luck. These are given in good faith. If you have any failures, it’s not my fault. These are tested, tried, and true. Love, Ellen.

I used to think this cousin must have simply been a little quirky. But then, people started telling me similar stories. Invariably at book events and cooking demos, someone would come up to me and say, “My grandmother’s bourekas were the best, but she refused to share the recipe with me!” Or “My mother-in-law’s marble cake was unparalleled, but I can never make it as tender as she did. She must have left out an ingredient so that my husband wouldn’t think I’m a better baker than his mom.”

While my evidence is decidedly anecdotal - and certainly plenty of grandmas freely pass along their wisdom - it seems there is some universality to this recipe hoarding phenomenon. But why wouldn’t they want to share?

My gut reaction is to get a bit angry. Food is memory! Food is culture! Food is love! By withholding their knowledge, these balaboostas are denying future generations of their heritage and closing the tap on generation-to-generation culinary transfer.

The more grownup parts of my brain (which I try, but don’t always succeed to access), seek out a more compassionate reason for their subterfuge. People derive a lot of meaning and identity from being “the cook of the family.” I imagine for a certain generation of (primarily women) cooks and homemakers, where the opportunities to make one’s mark were severely curbed by societal limitations and gender norms, it might have felt particularly hard to relinquish the sense of self worth found in feeding loved ones well and impressing guests.

Meanwhile, as a food writer and cookbook author who develops recipes for a living, I can say with authority that writing an accurate recipe is hard! Cooking is intuitive and improvisational. But crafting a recipe that will work consistently across a variety of kitchens is one part scientific (tablespoons, grams, temperature) and one part literary (“whisk until the batter is the consistency of heavy cream,” or “remove from the oven when the edges turn the color of caramel.”)

For people who are used to cooking from the hip - tasting, touching, and adjusting as they go - attempting to write down their process leaves ample room for error. In other words, maybe some of our grandmothers (or aunts, or parents, or cousins) left out an ingredient on purpose because they were spiteful or scared to let go of their power. But it’s far more likely they just made a mistake.

In preparation for this newsletter, I made the “Crunch Cake” from Ellen’s cookbook. Her instructions seemed mostly accurate, like her insistence to beat the butter and sugar together thoroughly. At 1 to 1 1/2 hours, however, the bake time seemed - and was - wildly too long. My cakes were quite done at around 55 minutes. Even in a slow oven, 1 1/2 hours would have been utterly disastrous.

The cake itself was...fine? It had a tender, poundcake-like crumb but was noticeably one-note in flavor, and not as interestingly textured as one might expect from a name like crunch cake. It was completely serviceable, but not earth shaking. Did cousin Ellen leave something out? You never know. But even the most carefully written recipes can’t take into account the changing tastes that come with time.

I decided not to share the recipe, because I would rather only share dishes here that I unequivocally love. (If you would like it, I’m happy to email it to you.) Instead, I’m linking you to a recipe for the Honey Apple Cake from my book, Little Book of Jewish Sweets, and leaving you with an exceptional - and very apropos - poem by one of my favorite Jewish feminist writers, Marge Piercy. I hope the cake (which I tested carefully, promise!) fills your belly this week, and the poem fills your soul.

My Mother Gives Me Her Recipe

By: Marge Piercy

Take some flour. Oh, I don't know,

like two-three cups, and you cut

in the butter. Now some women

they make it with shortening,

but I say butter, even though

that means you had to have fish, see?

You cut up some apples. Not those

stupid sweet ones. Apples for the cake,

they have to have some bite, you know?

A little sour in the sweet, like love.

You slice them into little moons.

No, no! Like half or crescent

moons. You aren't listening.

You mix sugar and cinnamon and cloves,

some women use allspice, till it's dark

and you stir in the apples. You coat

every little moon. Did I say you add

milk? Oh, just till it feels right.

Use your hands. Milk in the cake part!

Then you pat it into a pan, I like

round ones, but who cares?

I forgot to say you add baking powder.

Did I forget a little lemon on the apples?

Then you just bake it. Well, till it's done

of course. Did I remember you place

the apples in rows? You can make

a pattern, like a weave. It's pretty

that way. I like things pretty.

It's just a simple cake.

Any fool can make it

except your aunt. I

gave her the recipe

but she never

got it right.

Such a nice theme! Also: I loved this poem!!